A Manual for China Painters By Nicola di Rienzi Monachesi

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, painting china was a fashionable hobby. Unglazed or plain, ready-to-decorate porcelain items, called blanks, were available from Limoges, Lenox, Belleek and other sources. They were a canvas for floral, fruit, or landscape scenes. It was part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, turning mass produced china into personalized beautiful things. Some were made to resell, others were for personal use.

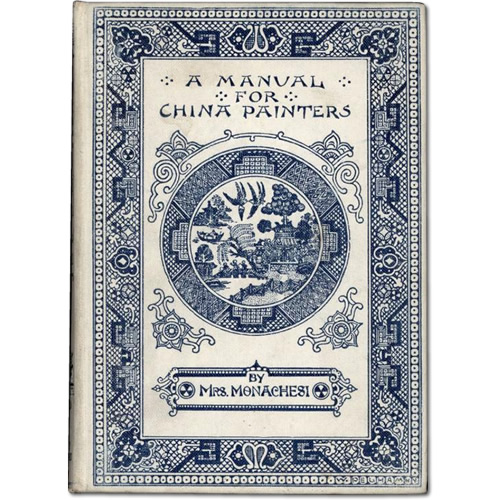

One of the sources for these amateur and professional artists. Is this book, A Manual for China Painters by Nicola di Rienzi Monachesi.

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

The original version of the book has a Blue Willow cover, making it a unique addition to a blue and white collection.

It is easy to find reprints on Amazon. Original versions can be found on eBay.

A Manual For China Painters by Nicola Di Rienzi Monachesi on Amazon

A manual for china painters, being a practical and comprehensive treatise on the art of painting china and glass with mineral colors

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

Publication date 1907

Here is some of the information you might find of interest.

Cobalt Blue

“Blues are made from cobalt …cobalt possesses a depth of rich color unequalled elsewhere, and is one of the colors that will stand the highest degree of heat.”

A Manual for China Painters, page 34

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

A Manual for China Painters, page 95

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

Tracing

If a design is to be copied exactly, tracing-paper will facilitate the process. In conjunction with the tracing-paper, there is often used a colored carbon or transferring-paper. Red or black is preferable. Both of these, however, have a soft, smutty surface, and make with the slightest pressure a thick, heavy mark, that is very undesirable. It is almost impossible to use it for fine work, like an intricate geometrical border, with thin, narrow lines, or for features of a small face, as in a Cupid.

There is a much better way of tracing and transferring the design to be painted, — a way in which this impression paper is dispensed with altogether. This method is not only easier and cleaner, but gives better and more accurate results.

Select a thin quality of tracing-paper, and, when about to use it, wipe both sides with a soft rag, slightly moistened with oil of lavender. This will make it still more transparent, and enable the amateur to see the copy better, and to follow the outlines more closely and clearly in every detail and feature of the subject. Place the tracingpaper over the design, and go over every outline with a sharp pointed lead-pencil, a soft one to be preferred, because a light stroke is all that is then sufficient. There is no necessity to use pressure, and with a hard pencil this is involuntarily done. This process demands considerable nicety and precision, and only experience will teach the value of extreme accuracy. Perhaps a slight deviation in the outlines of a floral design may not be observed, indeed, may not be incorrect; but to vary the lines of the human face would be fatal. A hair’s breadth would destroy a likeness, whether it be added or taken from, either eyes, nose, or mouth.

Having obtained a clean, clear, and correct reproduction of the copy, brush the back of the tracing lightly with powdered graphite. This is the same substance from which lead-pencils are made, and is reduced to an almost impalpable powder.

Very little is sufficient to be distributed over a large surface, and a superfluous quantity will produce unsightly and annoying smears over the china. As little as possible is to be used; just enough to give the paper a tinge of darkness, without being black.

If the paper be sufficiently moist with the lavender before the graphite be rubbed on, it is not necessary to use any turpentine on the china; but if this be neglected, the surface of the china must be wiped over with turpentine, and allowed to dry before attempting to transfer the design. This serves as a “tooth” and nicely takes every line; otherwise the china will not receive the impression.

Place the tracing-paper in the exact position, and fasten firmly to prevent slipping. This may be clone with wax, or strips of gummed paper, — the outer edges of a sheet of postage-stamps, where the mucilage has spread, answers this purpose admirably.

Then either with a very sharp pointed, hard lead-pencil, or stick, — as the end of a brush-handle whittled to a fine point, — go over each and every line before made, as indicated. An agate or ivory stylus is convenient for this purpose.

If these directions have been followed, it will be found, upon removing the paper, that a perfect picture is there, and an exact reproduction in outline of the copy.

The next thing to do is to go over the entire tracing on the china with india ink, using water and a very fine and pointed brush. This brush should be kept separate from the painting-brushes, and used exclusively for this purpose; and care should be taken to keep it straight and always to a point. This is done to secure the drawing, and provides beforehand against any unfortunate accident that necessitates wiping off the painting and commencing again.

The india ink line should exactly follow the tracing in a delicate, uniformly even, thin line.

After this is accomplished, a good plan, before commencing to paint, is to cleanse the china, and free it from every trace of graphite, and thus have a clean piece of china on which to work.

This is easily done by wiping it over with a rag slightly moistened with lavender. This evaporates immediately, and leaves the china in a beautiful condition to receive color.

This may seem a long, and perhaps even complicated, process; but it is the only process possible for those who are without previous instruction in the elementary rules of drawing, f

One of the essential features in all painting is first to obtain an accurate drawing; and, uninteresting as it may appear, the method herewith given for tracing is the easiest way of transferring the design. It requires time, considerable patience, and nice handling; but, when accomplished, half the battle is won.

The subsequent work will be comparatively easy. No detail should be omitted, as it will be found to be the very foundation to future success; and no amount of care and attention bestowed on the drawing is wasted.

A Manual for China Painters, pages 86- 91

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

Decalomania

The Blue Willow pattern is a mineral transfer using the mineral cobalt for the iconic blue.

Verifiable decalcomania or mineral transfers were formerly confined to potteries, but are now so readily procured and used that perhaps a few words may not be out of place here, as they certainly supply one way of decorating china.

It is not a very good or creditable style, however, nor one to be recommended, although many of the transfers are very pretty, graceful in design, and excellent in color, and in themselves artistic.

There are several reasons why they are used, the principal one probably being inability to do as well or produce as good results by ordinary methods.

Those who use them most assuredly save time and labor, a sufficient motive perhaps for self justification.

When this method of decorating china is resorted to with the intent to deceive, it at once becomes an imposture that is very deplorable. The fact that many people are unable to detect the print from the painted decoration is rather an unworthy excuse for duping an unsuspecting patron by taking advantage of his ignorance. Such tricking is beneath contempt.

Yet it would be unfair, if not unwise, to condemn this use, for mineral transfers have a well-defined place, and under some circumstances are perfectly legitimate. There are always two points of view. However, as this book claims to be one of practical instruction in the decoration of china, and not of morals, this is not the place to discuss the ethical side of the question.

These transfers are printed with mineral colors and consequently fire well and remain permanent. They come in two forms, single and duplex; the latter must be separated before applying to the china.

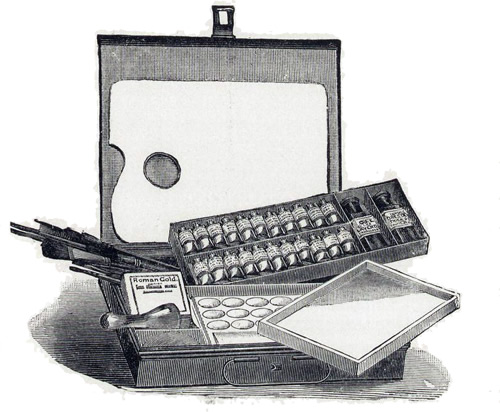

The materials and implements are, in addition to the transfer, the medium to make the transfer adhere to the china; a small roller; a sponge; a piece of chamois skin ; and a bowl of water.

The process is by no means complicated. Wet the chamois skin and spread out flat and smooth on the table, and upon this place the transfer face down, after cutting away all the margin. While this is becoming damp, take a brush and cover he china with the medium, not too thick or the transfer will blister in firing. The medium most probably is oil and turpentine, just as is usually employed when using mineral colors. Be sure the surface is entirely covered which is to be occupied by the transfer. In a few minutes it will become “tacky” and ready to receive the transfer.

Then carefully place the transfer face downward on the china without any hesitation. Put it down firmly where it is to go, and let it remain, because it cannot be shifted to another position and therefore must be placed exactly as it is intended. But if it is not on the right spot it must be left alone; under no circumstance attempt to move or change it.

Wet it thoroughly with the sponge and run the roller over it, from the center to the outside edge. See to it that it sticks closely. If any little bubbles or humps appear that will not down, prick them with the point of a very fine cambric needle. When the paper has become thoroughly saturated with the water, carefully lift it up, leaving the mineral film intact.

The duplex transfers can be made sufficiently smooth by gently patting or pressing, and the roller need not be used.

After removing the paper, submerge in the bowl of water and carefully wash, without tearing the transfer. Let it then stand a day or so to dry before firing.

After firing, the china is then to be treated exactly the same as though the picture had been painted. It can be touched up, worked over and around as desired.

Any background can be put in that suits the subject.

A Manual for China Painters, pages 249 – 252

By Monachesi, Nicola di Rienzi

Discover more from my design42

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.